FrederickHammersley

In Exploratory Programming for the Arts and Humanities, Nick Montfort considers computation to be a useful tool in a wide range of fields. [1] The projects that I describe here fit one category of practice that he writes about: programming as inquiry. Using a small set of code tools, it is possible to catalog and study Frederick Hammersley's use of Art1 in new ways that provide novel insights into his efforts and its results. Here, I use programs that can generate digital representations of Art1 images from archived code, even produce a sequence of Art1 images after each instruction card, or generate a heat map of Hammersley's activity from the archives. The results of this process can be compared back to what Hammersley himself said of his Art1 work. [2] My activities also rely on the digital repository of the Archives of American Art, web browsers, and other computational tools and infrastructure, further highlighting the significant but sometimes unseen role computation plays today in the arts and the humanities.

Frederick Hammersley's Art1 works

The Frederick Hammersley archives at the Smithsonian Institution's Archives of American Art hold over 200 Art1 printouts in addition to the final printed works. Each printout summarizes the data read into Art1 from the punch card set, including array initialization, title, and each drawing instruction. Below is a reproduction of a printout and corresponding Art1 image.

As you can see from the images above, it is possible to reconstruct Hammersley's works from the printout codes. Today it is more difficult (but perhaps not impossible) to print these on an IBM 1403 chain printer. The CSV file below is a listing of all of the printouts available in the online archives.

- FH_Art1_code.csv is a listing of the printout images in the archives.

Several of Hammersley's Art1 programs are available below as "card files". Each line in a card file (which is simply a text file, similar to any programming code) represents one 80-column IBM punch card.

Related topics

- About Art1 describes the Art1 program

- Art1 on Github is a compilable code base

- IBMSystem360 provides details about the mainframe originally used for Art1

Print dates

When Art1 runs, the first printed page is a summary of the data read into the computer. This "diagnostic" printout includes the date that the output was generated on the IBM mainframe. From these records, we can reconstruct when Hammersley submitted jobs to the UNM computer center for many (but not all) of his works. The printout dates often differ from the composition dates that he included in his title line, although 89 of the works aren't dated. The earliest print date in the archives is March 2, 1969 and the last date is June 5, 1971.

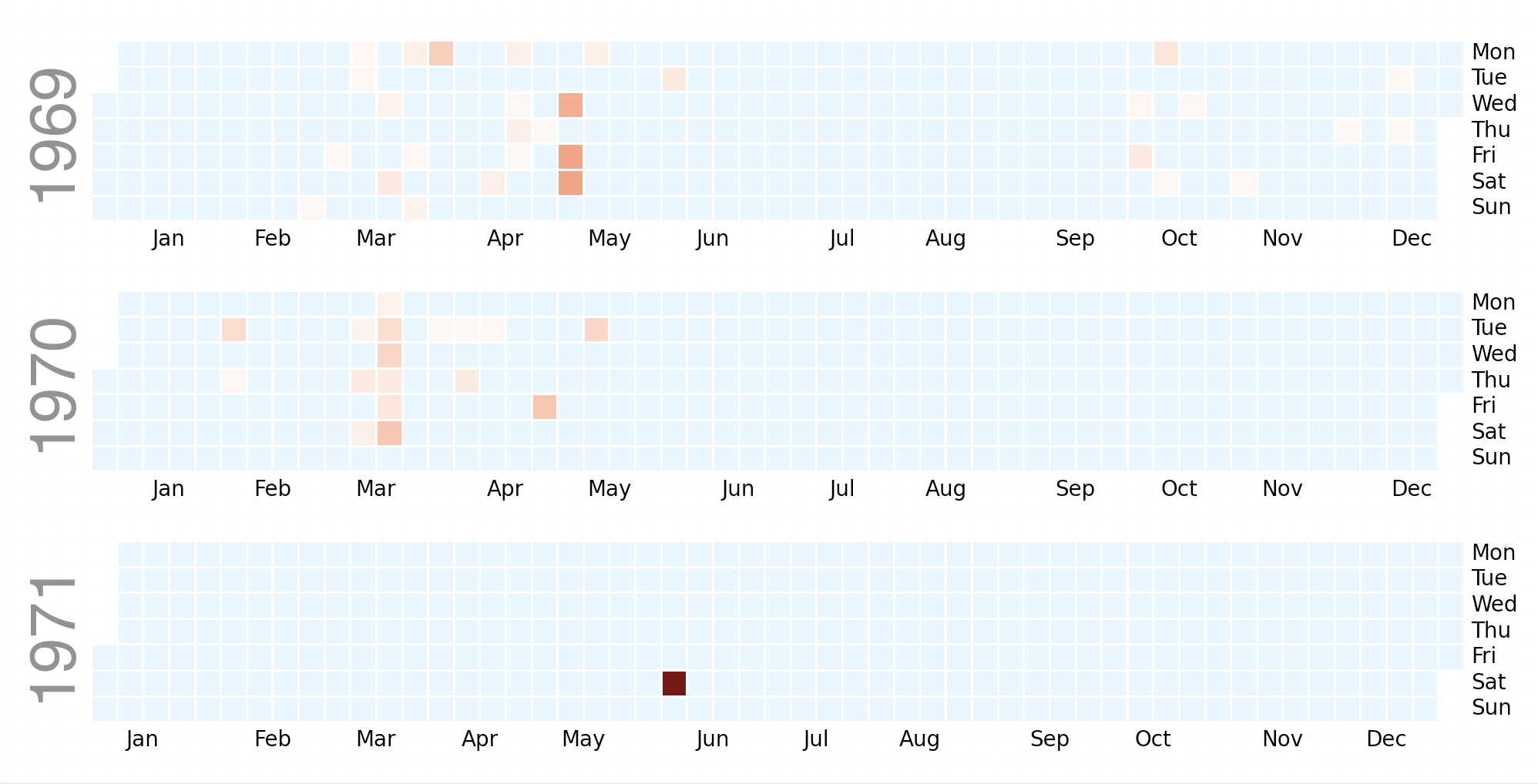

I constructed a Table that lists the number of prints Hammersley made on each date, but today a heat map is a more common way to visualize activity. Here is one corresponding to Hammersley's Art1 printing work from 1969-1971:

Hammersley's periods of work in 1969 and 1970 closely cluster in the academic calendar, with prints starting in the second half of the spring semester in 1969. [1] There are no Art1 printouts generated over the summer months of that year, but they resume in the fall and continue into the spring semester of 1970. This second year of work again clusters in the later half of the semester. In both spring terms, he was more active than in the fall. After his last print in May, 1970, Hammersley seems to have gone back to the computer center to print 32 of his works a year later. We see from the heatmap that Hammersley was especially active around the first week of May, 1969 and in mid-to-late March, 1970. The latter stands out, with a two-week burst of activity that culminates in the second week with six days of printing, including nine prints made on Saturday, March 21st. What were these works?

Of course, these dates don't reflect Hammersley's actual planning or thinking about Art1 -- that was done offline in sketches and hand-written codes, some of which survive in his papers. The earliest dated work in the Archive is CHARACTER REFERENCE (1/27/1969) and was printed on 3/22. The first work to be printed was TWO WAY STRETCH, dated 2/15/69 with a printout recorded on 3/2/1969. Hammersley was actively using Art1 earlier than these dates, though. In November 1968, he printed different overstrike patterns -- testing the capabilities of the program and developing his approach.

There is also activity in October and December 1969 that is notable for its separation from Hammersley’s other periods of activity. They invoke a mind at play, but perhaps in a subconscious mode, like a background process on a computer (a technology that would not emerge for some time after the late '60's.) The last pieces of this period are:

- UP TIGHT A LITTLE, 12/4/69

- GENTLY DOES IT, 12/16/69

- CONSTANT TEA TALK, 12/18/69

The October and November 1969 pieces include:

- SEEMS AINT, 10/8/69

- FLAR FROM PERFECT, 10/10/69

- 5 LINES FOR FLAR, 10/10/69

- TEA TALK, 10/10/69

- TEA TALK PAUSE, 10/10/69

- 5 ON A CLEAR MAZE, 10/13/69

- 5 LINES ON 5 SEEMS, 10/13/69

- TEA TIME ACROSS, 10/13/69

- STAGERD TEA & GAP, 10/13/69

- TEA TALK AND NINE, 10/13/69

- TEA TALK LION, 10/18/69

- NOT FLAR OFF, 10/22/69

- COOKIE CUTTER, 11/8/69

Heat maps are an interesting way to visualize creative activity across time, and should be useful for biographers, archivists, and bibliographers.

These files were all printed on 6/5/1971: THOUGHT HOLDERS, THOUGHT HOLDER, DO YOU ZEE, SCALLOP POTATOES, CO . ED, 5 ON A CLEAR MAZE, BUSY LION ON JELLY CENTER, ROUND PEG, FOUR TIMES AROUND, SEEMS AINT, SEEMLY YOU, YO..YO, NOT FLAR OFF, YO YO ALMOST, ADDED CHARACTER, EQUAL TEA TALK, YO YO WITH ENGLISH, COOKIE CUTTER, TEA TALK PAUSE, CHARACTER REFERENCE, GENTLY DOES IT, BUSY LION TO JELLY CENTER, TEA TALK BY TURNS, MYOPIC, HICCUP, CLAIROL, TO AMAZE, THE SAME CHANGE, SLEEPING PILL IT'S NOT, ROTISSERIE, ENOUGH IS PLENTY, JELLY CENTERS

Slicing compositions

The Art1 codes provide a glimpse of the structure of Hammersley's compositions – how he built up an image from the Art1 primitives. Wouldn't it be interesting to generate images as each Art1 command is processed? We could see the composition evolve like watching the brushstrokes of a painting. Did Hammersley imagine this process as he programmed Art1?

I wrote a short script that generates an image after processing each card in an Art1 program. The animated GIF below shows one example. As it cycles, it reveals layers of THE SAME CHANGE (85-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178566) after each programmed element is added to the composition. You can see that Hammersley used both additive and subtractive elements to build a fairly complex composition. There are a total of 12 cards in this drawing, including the initialization and "sentinal" cards. Eleven cards produce printed output.

Unlike a painting, however, the final Art1 print is not a physical composite of the programmed output encoded on the cards; it is only the result left in the two printable character arrays when the initializing card is processed. These images are visualizations of the AR1 and AR2 arrays as the program runs. In a sense, it is like sampling the core memory of the IBM System/360 after the machine processes each paper punch card.

"Slicing" a composition provides a method of studying Hammersley's process. We do have a few tantalizing details about the decisions he made, such as this passage describing "Enough is Plenty", his twenty-eighth drawing: [2]

I hope that simple code tools like these can provide fresh insight into Hammersley's work.

Related works

There are several series of Hammersley compositions that are related stylistically. [EMF: How are they related? Visually? By elements?] One general series is "TEA TALK." The compositions belonging to this family are sorted below by the AAA archive image name below.

| 153-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2179092 | CONSTANT TEA TALK | A |

| 98-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178792 | THE SAME CHANGE | A |

| 87-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178568 | THE SAME CHANGE | A |

| 85-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178566 | THE SAME CHANGE | A |

| 79-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178773 | TEA TALK BY TURNS | A |

| 75-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178769 | TEA TALK BY TURNS | A |

| 71-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178765 | TEA TALK PAUSE | A |

| 65-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178546 | TEA TALK LION | A |

| 63-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178544 | EQUAL TEA TALK | A |

| 61-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178542 | EQUAL TEA TALK | A |

| 59-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178540 | TEA TALK AND NINE | A |

| 56-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178537 | TEA TALK PAUSE | A |

| 54-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178535 | TEA TALK | |

| 53-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178534 | TEA TALK | |

| 50-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178531 | STAGERD TEA & GAP | |

| 49-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178530 | TEA TIME ACROSS | |

| 48-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178529 | TEA TIME ACROSS |

I found that 85-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178566 and 87-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178568 are identical files with the exception that the date (18 DEC 69) is included in the first and not in the latter. 71-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178765 and 56-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178537 are related this way, too. The date is missing in the latter copy and there are more prints (6), whereas the earlier only requests one. Hammersley must have gone back to make more copies of his work by re-running the cards with a new initializing card.

(Is 31-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178512.jpg SEEMS AINT related? Also: 33-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178514.jpg SEEMS AINT)

Card files

Files that can be processed by Art1. Each line in the file represents one 80-column card.

| File | Description |

|---|---|

| samechg.25 | THE SAME CHANGE |

| sai.25 | SEEMS AIN'T IS |

| teatalkpause.25 | TEA TALK PAUSE 2021 |

| 56-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178537.25 | TEA TALK PAUSE |

| 61-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178542.25 | EQUAL TEA TALK |

| 85-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178566.25 | THE SAME CHANGE |

| 87-AAA-AAA_hammfred_2178568.25 | THE SAME CHANGE |

Notes and references

- Nick Montfort, Exploratory Programming for the Arts and Humanities, 2nd ed., 2021. MIT Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- Frederick Hammersley, "My First Experience with Computer Drawings," Leonardo 2, 407--409 (1969).

- The academic calendar at the University of New Mexico today goes from late August to mid-December and resumes mid-January through mid-May.